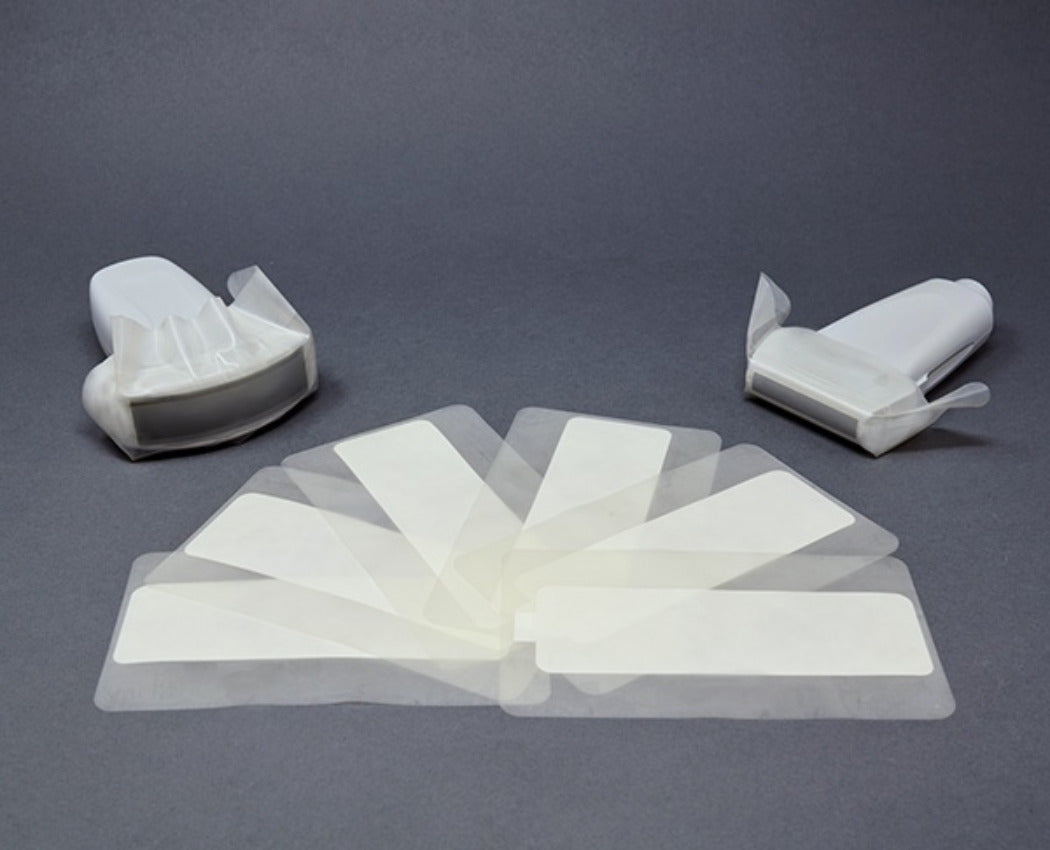

General Purpose Probe Covers

Available in sizes

ranging from 12 to 96 inches, our general purpose ultrasound probe covers cater to a variety of exams and procedures commonly used in emergency rooms, radiology departments, and vascular access clinics. These cost-effective

probe covers are all sterile and latex-free, made from either polyurethane

or polyethylene, and are designed for ultrasound probe infection prevention

in high-demand environments. For healthcare facilities with high patient

volumes, our disposable ultrasound probe cover kits, which include gel,

provide an efficient solution for infection control needs.

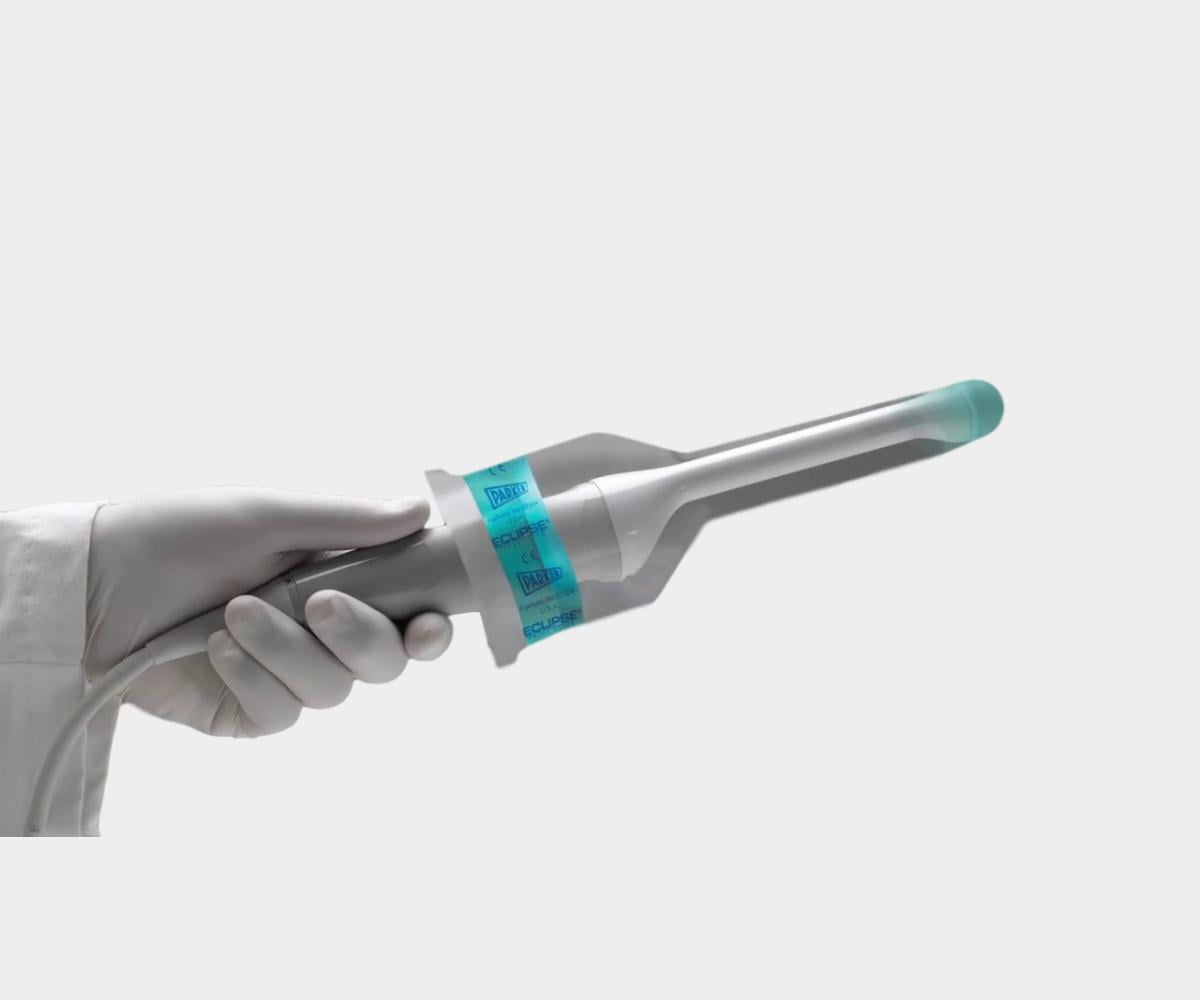

Endocavity Probe Covers

Our selection of endocavity ultrasound probe covers is specifically

tailored for transvaginal and transrectal ultrasound protection. These

covers, available in sterile and non-sterile options, come in both latex and

latex-free materials like PU or PIP, ensuring both ease of use and patient

comfort during sensitive exams. Designed to fit securely, they help provide

a reliable barrier against contamination for procedures requiring high-level

infection control.

Surgical Probe Covers

EDM’s sterile intraoperative probe covers offer surgical ultrasound protection in demanding surgical environments. Available in latex-free polyurethane or polyethylene, these 96" covers are ideal for operating rooms, effectively safeguarding patients, equipment, and healthcare staff from cross-contamination. These covers play a vital role in infection control protocols and are essential for high-risk procedures, making them a trusted choice for healthcare facilities focused on preventing healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs).

Explore our infection control products for additional surgical protection options.

Discover our range

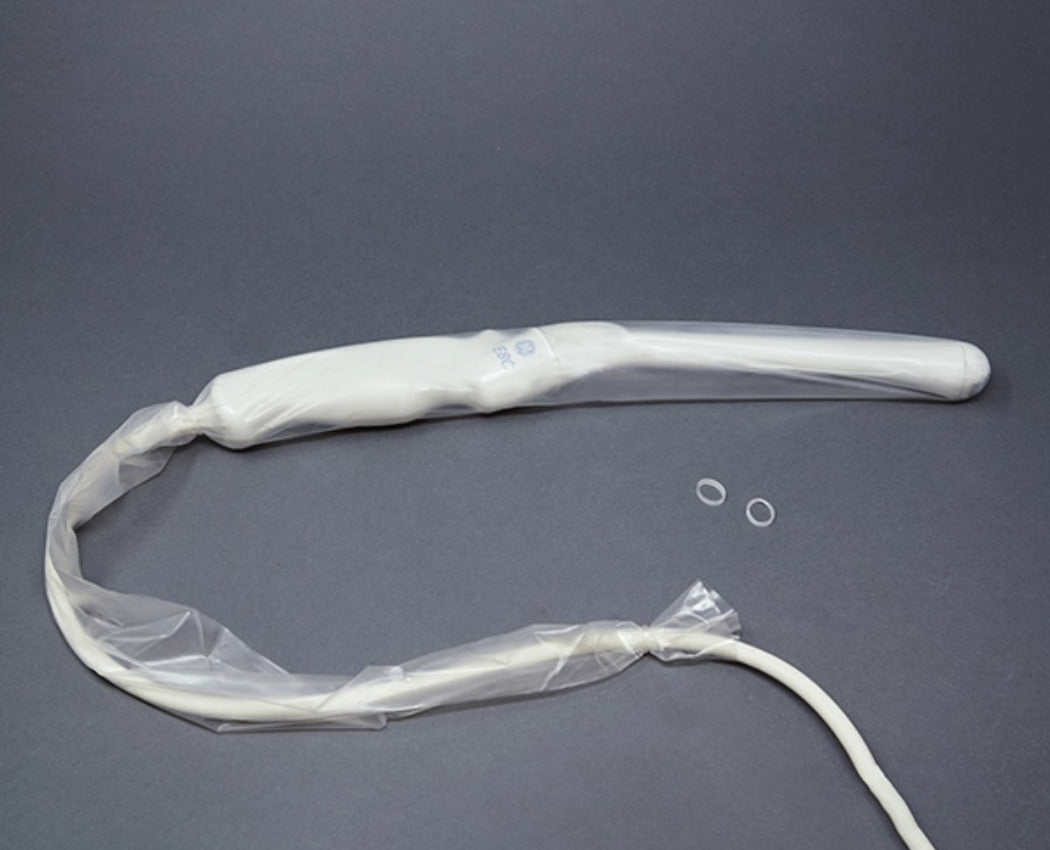

Probe Storage Covers

Our probe storage covers are designed to fit both endocavity and general-purpose probes, offering comprehensive protection that extends to the handle. Made from soft, flexible materials, they provide a secure barrier, shielding the probe from dust, debris, and contaminants during transportation and storage. These covers support sterile ultrasound probe storage protocols, ensuring that probes remain contamination-free, essential for ultrasound probe infection prevention practices.

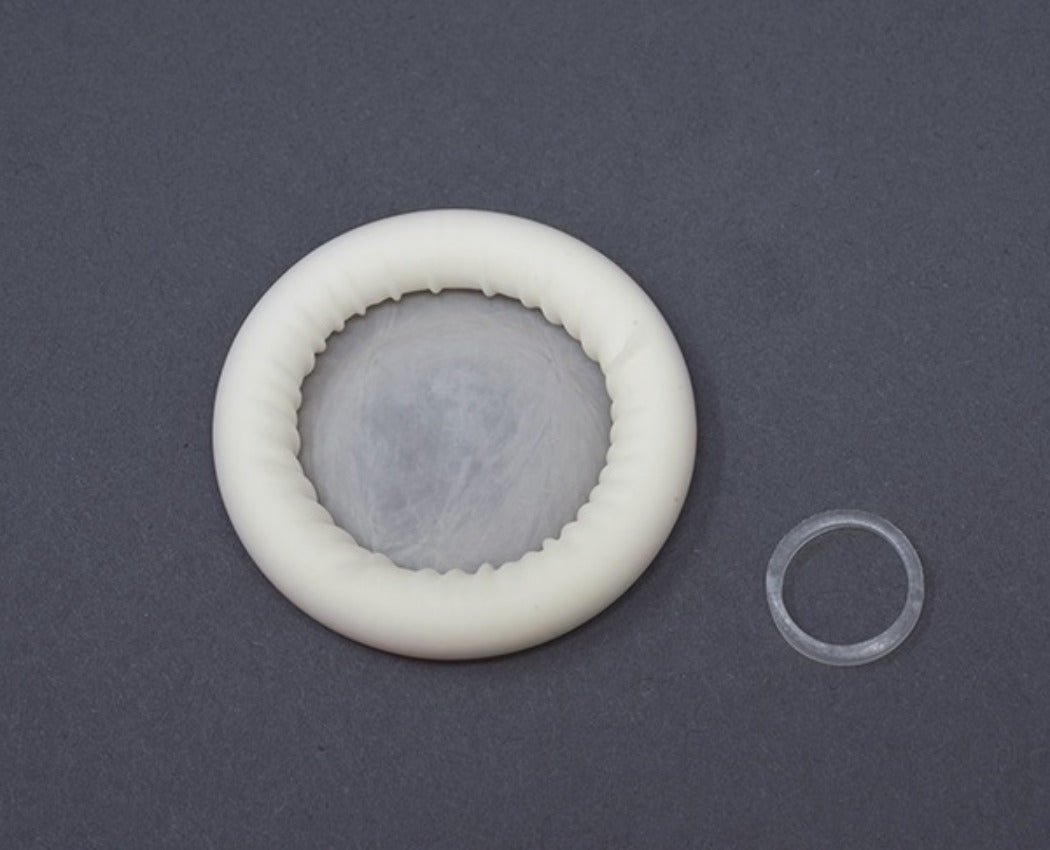

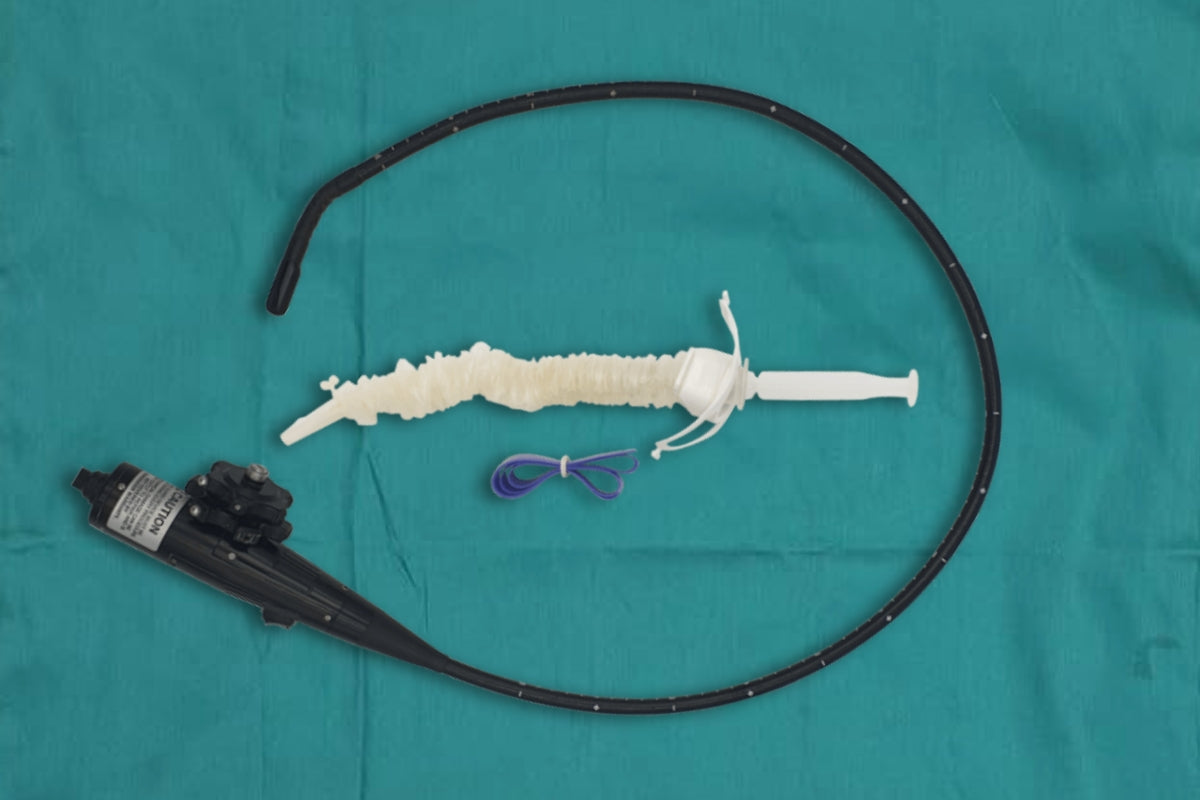

Discover our rangeTEE Probe Covers

Our TEE cover kits and system covers, ideal for transesophageal echocardiography procedures, are meticulously crafted from high medical-grade materials, providing cost-effective probe protection for portable ultrasound and tablet systems. EDM’s TEE covers give healthcare providers confidence in the quality and safety of their equipment, helping maintain strict infection prevention standards in critical care environments.

Discover our range

Infection Control and the Role of Ultrasound Probe Covers

As healthcare practitioners face an increased need for infection control, ultrasound transducer covers play a vital role in reducing healthcare-acquired infections by preventing cross-contamination.

Learn more about infection control best practices in ultrasound.

Learn more about infection control best practices in ultrasound.

Can an ultrasound probe cover substitute disinfection?

While ultrasound is regarded as a safe imaging modality, it presents infection control risks if not managed properly. Studies show that many facilities overlook the need to disinfect probes between patients. For instance, a study by the European Society of Radiology found that 29% of respondents did not disinfect ultrasound probes after each patient.

While many healthcare facilities view patient safety as a pressing concern, some may not realize the danger posed by ultrasound imaging. Since ultrasound does not expose patients to radiation, it has a reputation of safety and rightfully so. However, clinicians using ultrasound for their exams or procedures should be aware of the infection control threat it poses to their patients.

The infection control concerns surrounding ultrasound are the primary reason behind a variety of infection prevention guidelines which have been issued in recent years. The European Society of Radiology conducted a survey of its members and asked them a variety of questions regarding ultrasound infection control practices. One key finding of the study was frightening: 29% of respondents stated they did not disinfect the ultrasound probe after each patient.

It cannot be understated that ultrasound probes can very well be a vector of infection. The medical imaging community has witnessed the exponential growth of ultrasound in recent decades. While the general public may still associate the modality with prenatal checkups, gone are the days when ultrasound was primarily used by sonographers on pregnant women.

Ultrasound is now used widely across a variety of clinical areas, including urology, cardiology, and radiology. Physicians have found that the mobility and ease of use offered by the modality, especially point-of-care ultrasound, make it an ideal choice when taking the patient to the imaging suite is not the most suitable option. Ultrasound isn’t just present for exams either: the modality can now be found in interventional settings as well.

Moreover, ultrasound has now seen extensive use in emergency medicine and in the intensive care unit (ICU). During the COVID-19 pandemic, point-of-care ultrasound was a top pick for physicians examining and treating suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients. The ability to bring imaging into the patient’s room minimized the risk of infecting patients outside of the COVID-19 ward. However, its use in such a high-risk environment also signified new infection control threats.

With all this discussion surrounding ultrasound infection control, it is easy to lose sight of the best practices. Using ultrasound probe covers (sterile or non-sterile), the right kind of gel, and the appropriate disinfectant can reduce the risk of pathogenic transmission. But does using an ultrasound probe cover substitute disinfection? The short answer is no.

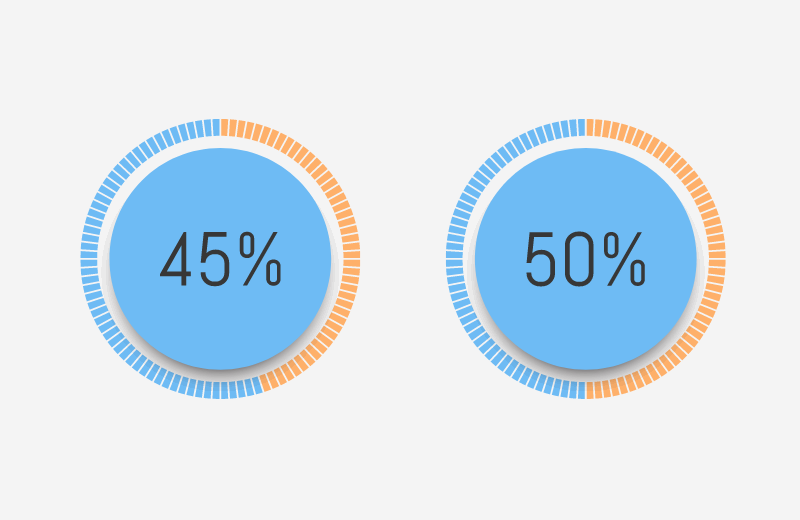

- Over 45% of ultrasound probes in five Emergency Departments (EDs) and ICUs showed bacterial contamination, with more than 50% showing traces of blood contamination (Keys et al., 2015).

- Approximately 1 in 31 patients in American hospitals faces the risk of contracting a healthcare-associated infection (HAI) daily. Adhering to proper infection control protocols can prevent many of these cases (CDC HAI Report, 2022).

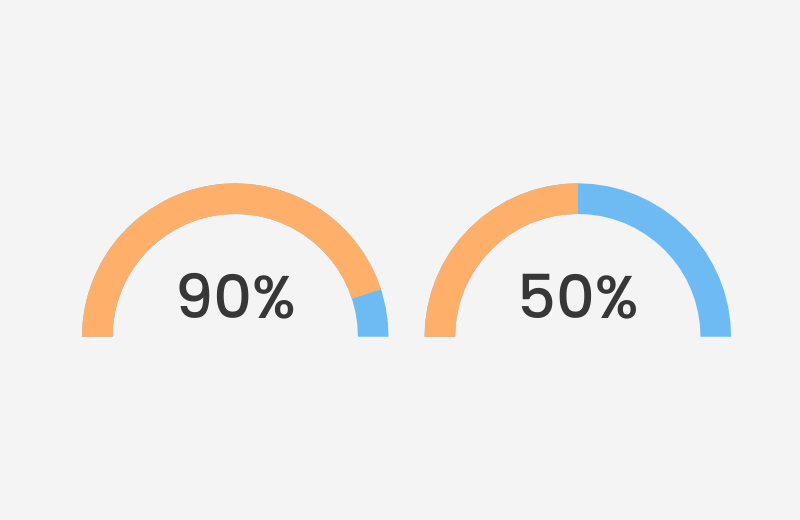

- Over 90% of cleaned transvaginal ultrasound probes were found to be contaminated, with more than 50% testing positive for MRSA or other pathogens (Oide et al., 2019).

Using the Spaulding classification to assess risk in endocavity exams and procedures

Ultrasound users should use the Spaulding classification to determine the appropriate level of disinfection and which probe cover should be employed. The Spaulding classification consists of three designations: critical, semi-critical, and non-critical. Each designation carries with it a recommended level of disinfection which practitioners should adhere too.

Endocavity ultrasound procedures may be categorized as semi-critical or critical depending on the nature of the procedure. The ultrasound can be considered semi-critical when it comes into contact with intact nonsterile mucosa or non-intact skin. On the other hand, critical is defined as when the ultrasound comes into contact with a sterile body cavity or tissue including the vasculature.

Thus, semi-critical encompasses transvaginal, transrectal, and transesophagael ultrasounds and any surface ultrasound which involves broken skin. Critical includes the use of probes in surgery, biopsies, punctures and drainages, vascular ablation, transvaginal oocyte retrieval, needle guidance, and venous catheter placement.

Upon establishing where your ultrasound-guided procedure falls under the Spaulding classification, clinicians should proceed to disinfect and protect the probe accordingly.

While sterilization is recommended for critical procedures, ultrasound probes cannot undergo sterilization due to the design of the device. As a result, be sure to use a high-level disinfectant (HLD) on the probe as this is the minimum level of disinfection for critical devices. It is also recommended that critical ultrasound probes be protected with a sterile ultrasound probe cover; however, it is not a requirement as non-sterile covers may also be used. Not only does using a probe cover prevent blood or other bodily fluids from contaminating the device, but it also preserves the sterile field and increases patient safety by creating a physical barrier between the device and the patient.

For semi-critical procedures, clinicians must perform high-level disinfection on the ultrasound probe. According to the Spaulding classification, HLD is the minimum requirement for reprocessing a semi-critical probe. Practitioners should note that HLD is able to kill all microorganisms except for bacterial spores. Endocavity ultrasound probes should also be protected with a cover, so as to prevent any contaminants from getting on the device. Common HLDs are glutaraldehyde, ortho-phthalaldehyde, and hydrogen peroxide.

Discover more about the Spaulding classification in ultrasound procedures.

View Endocavity CoversSources

1. Keys, M., et al. Crit Care Resusc. 2015:17(1): 43-46. Link

2. 2022 National and State Healthcare-Associated Infections Progress Report. Link

3. Oide, S., et al. (2019). J Med Ultrason 46(4): 475-479. Link

4. European Society of Radiology study on infection control. Link

5. Infection control best practices in ultrasound. Link

6. Study on bacterial contamination of ultrasound probes. Link

7. CDC Healthcare-Associated Infections Progress Report. Link

8. Spaulding classification for ultrasound-guided procedures. Link

9. Guidelines for Infection Prevention and Control in Sonography: Reprocessing the Ultrasound Transducer. Link

10. Infection prevention and control in ultrasound - best practice recommendations from the European Society of Radiology Ultrasound Working Group. Link