At the 2019 meeting of the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), researchers offered key insights into how focused ultrasound can potentially be a safe and effective way to target and open areas of the blood-brain barrier. Doing so could permit for new treatment approaches to Alzheimer’s disease.

The blood-brain barrier is a network of blood vessels and tissues that stops foreign substances from entering the brain. The barrier poses a challenge for scientists researching Alzheimer's treatments, because it does not allow potentially therapeutic medications to reach target areas within the brain.

Many researchers have been looking into the use of ultrasound as a treatment option for various diseases, such as diabetes.

The group behind the study have been researching the effects of low intensity focused ultrasound (LIFU) in patients with Alzheimer’s disease for more than a year. The clinical trial has been led by Ali Rezai, M.D., Director of the West Virginia University (WVU) Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute.

In the study, researchers performed low intensity focused ultrasound (LIFU) on target areas of the brain critical to memory in three women, ages 61, 72, and 73, with early-stage Alzheimer’s. The participants also had evidence of amyloid plaques – abnormal clumps of protein in the brain that are linked with Alzheimer’s. Each participant received three ultrasound treatments at two-week intervals and were monitored for bleeding, infection, and edema.

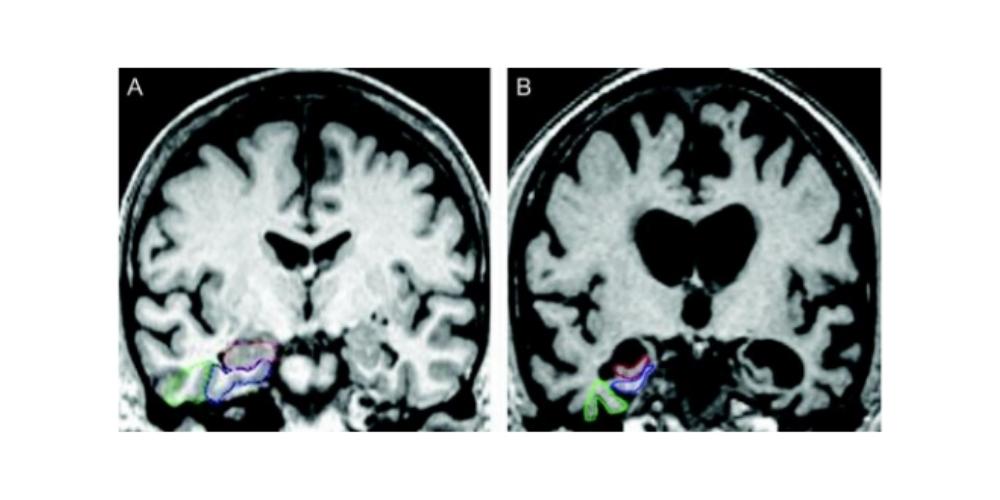

Researchers performed a post-treatment MRI on the brain of each participant. The MRI revealed that the blood-brain barrier opened within the target areas after the ultrasound treatment and then closed after 24 hours.

“Different techniques have been attempted to open the blood-brain barrier, but a lot of those techniques have adverse effects or are general,” wrote co-author Rashi Mehta, M.D., associate professor at WVU and research scholar at West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute. “To open it in one specific area of the brain is a challenge and that is something that this technology overcomes.”

The authors went on to explain the process behind the new ultrasound treatment. LIFU consists of placing a helmet over the patient’s head after they are positioned in the MRI scanner. This helmet is then equipped with more than a thousand separate ultrasound transducers pointing in different directions. Each transducer delivers sound waves which are directed to a target area of the brain. During the procedure, patients are given an ultrasound contrast agent intravenously that is made up of microbubbles. These go changing in size and shape as the ultrasound is applied. Dr. Mehta said this oscillation results in transient loosening of the blood-brain barrier, which they documented using gadolinium contrast enhanced MRI.

“We monitor how well the bubbles are doing in real time,” said Jeffrey Carpenter, M.D., professor at WVU and a co-author on the study. “We have microphones that are set up that are listening to the bubbles vibrate and we actually base how much ultrasound energy we give on what the bubbles are doing.”

The study is in a phase two clinical trial focused on the safety and efficacy of the ultrasound treatment in opening the blood brain barrier. However, Dr. Mehta is confident and expects future trials to involve delivering clinical drugs.

“Future trials undoubtedly will evaluate a combination of this with therapeutics,” Dr. Mehta said. “This could be a new technique of delivering medication to the brain in general for all sorts of diseases.”

As of now, the study will continue with a larger cohort before phase two is closed out. Moreover, Dr. Mehta reports that the research team is interesting in observing how effective LIFU would be alone in potentially altering the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Thus, the group is following each patient post-treatment to keep an eye on their amyloid beta levels with PET imaging. It is, however, too early for the team to report on this and their hope is to follow each participant for five years.

The research team has begun to plan phase three of the trial while still seeking Alzheimer’s patients to complete phase two. By the end of the second phase, the trial will have involved a total of ten participants at WVU, Cornell, and Ohio State.

“We just really want to show that this can be done repeatedly and safely, and then add onto that in the future with hopefully various medications, stem cells or whatever smart people can come up with,” Carpenter said. “The fact that we could do this repeatedly — three patients three times — so total of nine times safely with no hemorrhage, no persistent edema, and the blood-brain barrier closes — that’s a big deal.”